Leica is Proving the Mark of a First-Rate Camera Company is the Ability to Hold Two Conflicting Ideas at the Same Time

With apologies to F. Scott Fitzgerald, who famously wrote that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function,” I’ve been thinking a lot this year about what Leica Camera is up to.

Leica is, comparatively speaking, a tiny company — they measure revenue in the millions, not billions, and produce cameras and lenses in small batches. And yet they currently have the moxie to produce a 64mp medium format camera system (the S), a professional mirrorless camera system (the various SLs, along with their L-Mount little brother, the CL), their traditional rangefinder system (the M, in color and monochrome variants), and even a certifiable hit product, the Q2, which just spawned a Monochrom (B+W only) twin. On top of it all, in the very same calendar year, Leica released the M 35mm APO-Summicron, which is as precise and perfect a compact lens as exists on this planet, and what can only be thought of as its near antithesis: a “classic” reprise of its 1966 M Noctilux f/1.2 ASPH, a lens whose charm lies almost entirely in the idea that it is *not* perfect.

So yes, in the immense combined brainpower that is Leica’s product team, they are proving Scott Fitzgerald right, or at least proving their first-rate intelligence, as they continue to astound us with a lens roadmap that brings out lenses so astonishingly perfect there are those who call them antiseptic (e.g. the M 50mm APO-Summicron, both the M and SL versions of the 35mm APO, as well as each of the SL APO Summicron primes), while working into the mix modern revivals of some of their most intriguing lenses from decades past, whose charm lies in how their flaws intersect with new cameras housing 47mp modern sensors.

I’ve been using Leica Ms for long enough to remember the debate in the early ’00s over not whether Leica could produce a digital M, but whether they should. At one point, their largest shareholder, the luxury brand Hermes, purportedly counseled management to stick with film and become the 21st Century equivalent of a Parisian saddle maker, locked into high profits, but decreasing relevance to anyone other than a plutocrat. Thankfully, under the stable ownership of Dr. Andreas Kaufmann, Leica, since 2006, has been an absolute font of creativity. Of all the camera systems listed above, only the M existed in that year. And when what became known as the M-240 was released in 2013, by switching to CMOS sensors — which permitted the use of Leica’s R-system lenses — rangefinder photographers could suddenly use virtually every lens that Leica had produced since the 1950s.

The image above, to me, captures something quite magical. It was made using a 41mp Leica M10 Monochrom with a state-of-the-art sensor, but coupled with a 35-year old R-system lens. I think the combination has a timeless feel to it, and could imagine it used in a magazine spread on Jackson Hole, circa 1963. Because the lens cannot remotely draw as precisely as the sensor might receive the captured data, it combines imprecision with precision along a formula similar to the way Leica’s then-state-of-the-art cameras and lenses, from the 1930s to the digital era, drew on film. Evidently Leica thinks such old/new and perfect/imperfect combinations might hold buyers’ interest, which is why they have, in the last few years, released such lenses as a reprise of their 28mm f/5.6 lens from decades ago, and even the Thambar, which can only be described as a willfully distorting, extremely soft lens. Which brings us to February’s release of the “new” 50mm Noctilux f1.2.

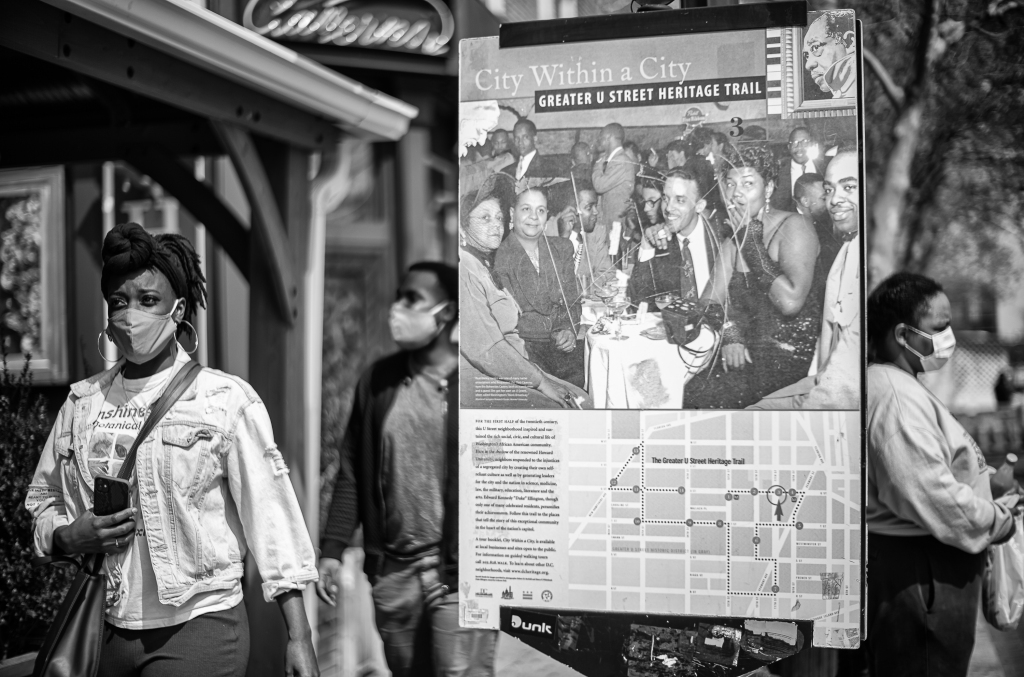

This past winter and spring, I immersed myself in a street photography project in an historic D.C. neighborhood. Everything was shot using the Leica M10 Monochrom, and for the most part, the 28mm Summicron, 35mm Summilux, and occasionally, the 50mm APO-Summicron. Now, I am a Noctilux photographer with 15 years experience utilizing Leica’s low-light, thin focal-plane lens. But I would almost never consider using my 75mm Noctilux f1.25 on the street, because it is so big and bulky; it’s a physical chore, not to mention negating the stealth aspect of using an M in those circumstance. But the early word, vouchsafed by reviewers such as Sean Reid and Jono Slack, was that the new 50mm Noctilux f/1.2 ASPH was about as small as a 50 Summilux, quite light, and while it had nowhere near the precision of the 50 Nocti f/0.95 or my 75 Nocti, it had beguiling characteristics. So, I jumped, and traded in some equipment to buy it. And I found it immediately appealing. I mean, the first time I looked at the LCD on the camera to see what had been captured, I broke out into a grin.

I could take my Monochrom with the new Nocti out on the street and remain relatively invisible. And while this lens certainly was soft in its rendering of the in-focus areas, because it also captures that glorious fall off to the out-of-focus area, there was something genuinely exciting about it, at least to me. One of the paradoxes of modern photography is how so many of us revel in the advantages of the digital revolution, which often results in clinically over-precise images, which we then work on in post-production software to render “film-like.” We want all the advantages of digital capture, but harken for the imprecision of classic photography on the far more forgiving sensor of celluloid processed in wet chemicals.

Leica, by virtue of making such incredible fast lenses, has always been at the forefront of a related aspect of visual poetry — the use of bokeh as a dramatizing technique. I wouldn’t say the image above is a great shot, technically. But in terms of creating atmosphere, using a black and white 41mp sensor and a deliberately soft lens with a drop off from the in-focus to OOF area that plunges with a depth and speed of Niagara Falls is, to my eye, fairly special. And I could carry the lens on the street!

I didn’t use it exclusively, and the project is better off for it, as there is wide variety between the many images shot at, say, f/8 and fairly small batch shot at f/1.2. (All Noctiluxes are, effectively, single f/stop lenses — you shoot them wide open or not at all.) But man, this lens was cool on the street!

There was something about its imprecision that rendered it in a category separate from the other modern Noctilux lenses. Now, you see, I was deep into a black and white project, which right there rendered it in alignment with photography from eras past. But the more I used this lens, the more I could see it helped evoke the fairly gritty neighborhood I was in, while capturing a moment in time: people wearing masks will always anchor these images in our COVID age. I wanted to ensure that if, 50 years from now, people looked at these images they would immediately place a time stamp on them — and for that reason, shooting in black and white was essential. Increasingly, the new Nocti seemed an ideal tool to bring to the mix.

The image above, shot in March 2021, to me has the classic feel of an image that could have been shot on an M4 using the original ’66 Nocti and Tri-X Pan. That’s a hard trick for a modern 41mp sensor to pull off, without Lightroom skills far beyond my capabilities.

When the weather turned warm and cherries blossomed, I deliberately forced myself to take a break from my project to use this lens with a camera that could record in color as well: the M10-R. The result was every bit as interesting to me, the color rendering weirdly compelling.

In early summer, my wife and I moved pretty much full-time to a small town in Western Wyoming, and I took the Nocti to the 4th of July parade there. To be honest, I think I would have taken more good pictures if I’d used the lens with the SL2, not the M10-R, because I would have been able to focus more precisely. But still, its color rendering with the M10-R sensor is quite nice.

Having used the lens to shoot black and white on the streets of Washington, and now color at the Jackson, Wyoming 4th of July parade, I think I have an understanding of the 50mm Noctilux f/1.2 ASPH’s strengths and weaknesses. Its strengths are: small size and weight, making it ideal for street photography, its seductive bokeh, and when combined with a precise modern sensor on a digital camera, its imprecision, soft in-focus area, and characteristic drop off to the out-of-focus area renders the image with a timeless patina. This is, getting back to Leica, redolent of their understanding that we don’t want, at least not all the time, perfection in certain kinds of photography. We want character. This lens has it in abundance.

But what if you do want perfection, or at least sharpness in the in-focus area? Going back to 2012, when Leica announced the original M Monochrom, they coupled it with a brand new lens, the 50mm APO-Summicron. They said, in essence, because we have stripped the sensor of its responsibility to convert pixels to color, it will be a meaningfully more capable sensor than what we have in the then-flagship M9. And then, to illustrate this point, they released their new APO-Summicron lens, and in their nice way, sort of boasted that they had taken optical performance to a new and unheard of level, matching the possibilities in digital sensor design.

What that really meant was that the new APO-Summicron was so sharp in its in-focus rendering, while still maintaining a classical drop off from the focal plane, that a different kind of alchemy was possible. About as expensive as the Noctilux, the new 50 APO was startlingly perfect whether shooting wide open or stopped down. But it strived for a far different gestalt from the Nocti: perfect and imperfect wrapped into one package, which, when coupled with the second generation Monochrom sensor let the photographer achieve things heretofore unimaginable. It was almost as if it was challenging our conception of what great photography consisted of, as if to say, We can achieve optical perfection and, in the camera, the highest quality, and you, the photographer, can make images that will retain the same luster as what HC-B was able to achieve in the streets of Paris in 1938.

I for one bought into this wholeheartedly, and used the 50 APO a lot, whether in the streets or shooting landscapes. Which is why when Leica announced, literally weeks after the 50 Noctilux f/1.2 ASPH, that they were releasing a 35mm APO, my heart beat quickly, even as it sank with the understanding that I would have to sell more equipment to acquire the new reference point in optical perfection. You see, 35mm is my favorite focal length. So it was worth selling other lenses to get my hands on what proved to be a very, very difficult lens to acquire. (As I mentioned earlier, Leica produces cameras and lenses in small batches.) It took a little more than four months.

On the happy day it was to arrive, I waited a long time for the UPS truck to show up — but one walk in my rural neighborhood showed me the 35mm APO set, as Leica stated, a new standard. Its color rendering was typical for Leica’s APOs, whether M or SL. Coupled with M10-R, it seemed like it would become the lens I would keep on my rangefinders by default.

The next night, I took it to the local rodeo and, combined with the M10-R, realized I had in many ways as capable a combination as the Leica SL2 and SL 35mm APO, albeit in a package small enough for street photography.

As with the 50mm APO, what was in focus was precise, and where the focus fell off, you could have fun.

This was a lens for the ages — amazing color rendering and precision, in as compact a form as the 35mm Summicrons from the last several decades.

Perhaps I shouldn’t fall into the marketing hype of calling this lens “perfect.” I will say only this: in combination with the M10-R, it achieves street photography nirvana. I have stuck with Ms because I am by now so comfortable with focusing manually, or shooting at the hyperfocal distance, that I believe I can utilize the technology more intuitively and just as fast as I would if using, say, the autofocus Leica Q2. I’ll admit to going “wow” when seeing how the Q2 lens and sensor renders images, especially in color, and the new Q2 Monochrom seems amazing. And yet, with the 35 APO on the M10-R, I don’t think the Q system has any advantages.

So here you have a lens that can be shot at f/4 and retain great character. This is anything but “clinical”, even though it may be optically “perfect.” This is a lens for the ages.

And if it is a standout given the way it handles color, I must say its B&W rendering is pretty satisfying. It has the added advantage of being so small, and in combination with an M, so light and capable, that I now find myself hiking with just the M and a single lens, not the SL2 and some of those big native zooms. Am I missing anything by not taking the SL2? Well, sure, of course — it’s a more capable, versatile system. But at the same time, nah. And, at the end of the day, my neck and arms thank me for carrying the lighter camera and lens.

I’ll conclude with this. To me, Leica has proved — over the last several years, but particularly in a 2021 in which it could release, back to back, both the 50mm Noctilux f/1.2 ASPH and the 35mm APO-Summicron — that it understands the modern photographer’s love/hate relationship with “perfection.” It *gets* our desire to create images that are half as enchanting as something Saul Leiter or Sergio Larrain would have captured in the 1950s — using the equipment available to them then. (Our skill and talent are, of course, quite different from theirs…)

The point is that the power and raw capabilities of modern sensors and modern lenses can bleed a little of the poetry from the pictures we take — which is one reason why we work so hard in Lightroom to achieve that paradoxical goal of making an image “film-like.”

To their immense credit, Leica — a company owned by a photographer and run by photographers, including the lens-designing genius Peter Karbe — wants to innovate in both directions. With the near simultaneous release of these two lenses, they have achieved making perfection and magic something other than antonyms. They have learned to drain my bank account but give me great pleasure through the tools they offer. They have held two seemingly opposing ideas in mind while retaining the ability to function. Oh, brother, have they ever.

John Buckley is a photographer in Wilson, WY and Washington, D.C. His Instagram is @tulip_frenzy, and his photography website is JohnBuckleyinBlackandWhiteandColor.com. His photobook Pictures of U: Six Months in an Historic D.C. Neighborhood will be published in late 2021.

August 14, 2021 at 9:51 pm

Great article under all the aspects.

It’s a pleasure, always, reading “you”.